- Home

- John Sandford

The Hanged Man’s Song

The Hanged Man’s Song Read online

The Hanged Man’s Song

John Sandford

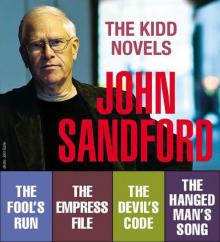

This series of techno-suspense novels featuring artist, computer wizard and professional criminal Kidd (The Fool’s Run; The Empress File; The Devil’s Code) and his sometime girlfriend, cat-burglar LuEllen, are far fewer in number and less well-known than Sandford’s bestselling Prey books. In this entry, Bobby, Kidd’s genius hacker friend (“Bobby is the deus ex machina for the hacking community, the fount of all knowledge, the keeper of secrets, the source of critical phone numbers, a guide through the darkness of IBM mainframes”), goes offline for good when he is hammered to death by an intruder. Bobby’s laptop is stolen, which is bad news for Kidd as several of his more illegal transactions may be catalogued on the hard drive. Kidd needs to find the computer, break the encryption and revenge Bobby’s death. The trail leads from Kidd’s St. Paul, Minn., art studio to heat-stricken rural Mississippi and on to Washington, D.C., where Kidd uncovers a government conspiracy that threatens the reputations and livelihood of most of the nation’s elected representatives. One of the joys of the series is learning the tricks of computer hacking and basic burglary as Kidd and LuEllen take us to Radio Shack, Target, Home Depot and an all-night supermarket to buy ordinary gear, including a can of Dinty Moore Beef Stew, to use in clever, illegal ways. The action is as hot and twisted as a Mississippi back road, but the indefatigable Kidd eventually straightens it all out and exacts a sort of rough justice that matches his flexible moral code. The early entries in this series have aged badly because of the advances in technology, but this latest intelligent and exciting thriller proves a worthy addition to Sandford’s overall body of work.

John Sandford

The Hanged Man’s Song

The fourth book in the Kidd And LuEllen series, 2003

THIS ONE IS FOR MY FELLOW HOSERS AT THE ST. PAUL PAPERS.

YOU KNOW WHO YOU ARE.

Chapter One

NOW THE BLACK MAN screamed No!, now the black man shouted, Get out, motherfucker, and Carp, a big-boy at thirty, felt the explosion behind his eyes.

Tantrum.

They were in the black man’s neatly kept sick-house, his infirmary. Carp snatched the green oxygen cylinder off its stand, felt the weight as he swung it overhead. The black man began to turn in his wheelchair, his dark eyes coming around through the narrow, fashionable glasses, the gun turning, the gun looking like a toy.

And now it goes to slo-mo, the sounds of the house fading-the soprano on public radio, fading; the rumble of a passing car, fading; the hoarse, angry words from the black man, fading to inaudible gibberish; and the black man turning, and the gun, all in slo-mo, the sounds fading as time slowed down…

Then lurching to fast forward:

“HAIYAH!” James Carp screamed it, gobs of spit flying, one explosive syllable, and he swung the steel cylinder as hard as he could, as though he were spiking a football.

The black man’s skull shattered and the black man shouted a death-shout, a HUH! that came at once with the WHACK! of the cylinder smashing bone.

The black man spun out of his wheelchair, blood flying in a crimson spray. A.25-caliber automatic pistol skittered out of his fingers and across the red-and-blue oriental carpet into a corner; the wheelchair crashed into a plaster wall, sounding as though somebody had dropped an armful of pipes.

Time slowed again. The quiet sounds came back: the soprano, the cars, an airplane, a bird, and the black man: almost subliminally, the air squeezed out of his dying lungs and across his vocal cords, producing not a moan, but a drawn-out vowel oooohhhh…

Blood began to seep from the black man’s close-cut hair into the carpet. He was a pile of bones wrapped in a blue shirt.

CARP stood over him, sweating, shirt stuck to his broad back, breathing heavily, angry adrenaline burning in his blood, listening, hearing nothing but the rain ticking on the tin roof and the soprano in the unintelligible Italian opera; smelling the must and the old wood of the house tainted by the coppery odor of blood. He was pretty sure he knew what he’d done but he said, “Get up. C’mon, get up.”

The black man didn’t move and Carp pushed the skinny body with a foot, and the body, already insubstantial, shoulders and legs skeletal, small skull like a croquet ball, flopped with the slackness of death. “Fuck you,” Carp said. He tossed the oxygen cylinder on a couch, where it bounced silently on the soft cushions.

A car turned the corner. Carp jerked, stepped to a window, split the blinds with an index finger, and looked out at the street. The car kept going, splashing through a roadside puddle.

Breathing even harder, now. He looked around, for other eyes, but there was nobody in the house but him and the black man’s body. Fear rode over the anger, and Carp’s body told him to run, to get away, to put this behind him, to pretend it never happened; but his brain was saying, Take it easy, take it slow.

Carp was a big man, too heavy for his height, round-shouldered, shambling. His eyes were flat and shallow, his nose was long and fleshy, like a small banana. His two-day beard was patchy, his brown hair was lank, mop-like. Turning away from the body, he went first for the laptop.

The dead man’s name was Bobby, and Bobby’s laptop was fastened to a steel tray that swiveled off the wheelchair like an old-fashioned school desk. The laptop was no lightweight-it was a desktop replacement model from IBM with maximum RAM, a fat hard drive, built-in CD/DVD burner, three USB ports, a variety of memory-card slots.

A powerful laptop, but not exactly what Carp had expected. He’d expected something like… well, an old-fashioned CIA computer room, painted white with plastic floors and men in spectacles walking around in white coats with clipboards, Bobby perched in some kind of Star Wars control console. How could the most powerful hacker in the United States of America operate out of a laptop? A laptop and a wheelchair and Giorgio Armani glasses and a blue, freshly pressed oxford-cloth shirt?

The laptop wasn’t the only surprise-the whole neighborhood was unexpected, a run-down, gravel-road section of Jackson, smelling of Spanish moss and red-pine bark and marsh water. He could hear croakers chipping away in the twilight when he walked up the flagstones to the front porch.

RIGHT from the start, his search seemed to have gone bad. He’d located Bobby’s caregiver, and the guy wasn’t exactly the sharpest knife in the dishwasher: Carp had talked his way into the man’s house with an excuse that sounded unbelievably lame in his own ears, so bad that he couldn’t believe that the man had been trusted with Bobby’s safety. But he had been.

ANY question had been resolved when Bobby had come to the front door and Carp had asked, “Bobby?” and Bobby’s eyes had gone wide and he’d started backing away.

“Get away from me. Who are you? Who… get away…”

The whole thing had devolved into a thrashing, screaming argument and Carp had bulled his way through the door, and then Bobby had sent the wheelchair across the room to a built-in bookcase, pushed aside a ceramic bowl, and Carp could see that a gun was coming up and he’d picked up the oxygen cylinder.

Didn’t really mean to do it. Not yet, anyway. He’d wanted to talk for a while.

Whatever he’d intended, Bobby was dead. No going back now. He moved over to the wheelchair, turned the laptop around, found it still running. Bobby hadn’t had time to do anything with it, hadn’t tried. The machine was running UNIX, no big surprise there. A security-aware hacker was as likely to run Windows as the Navy was to put a screen door on a submarine.

He’d figure it out later; one thing he didn’t dare do was turn it off. He checked the power meter and found the battery at 75 percent. Good for the time being. Next he went to the system monitor to look at the hard drive. Okay: 120 gigabytes, 60 percent full. The damn t

hing had more data in it than the average library.

The laptop was fastened to the wheelchair tray by snap clamps and he fumbled at them for a moment before the computer came loose. As he worked the clamps, he noticed the wi-fi antenna protruding from the PCMCIA slot on the side of the machine. There was something more, then.

He carried the laptop to the door and left it there, still turned on, then went through the house to the kitchen, moving quickly, thinking about the crime. Mississippi, he was sure, had the electric chair or the guillotine or maybe they burned you at the stake. Whatever it was, it was bound to be primitive. He had to take care.

He pulled a few paper towels off a low-mounted roll near the sink and used them to cover his hands, and he started opening doors and cupboards. In a bedroom, next to a narrow, ascetic bed under a crucifix, he found a short table with the laptop’s recharging cord and power supply, and two more batteries in a recharging deck.

Good. He unplugged the power supply and the recharging deck and carried them out to the living room and put them on the floor next to the door.

In the second bedroom, behind the tenth or twelfth door he opened, he found a cable jack and modem with the wi-fi transceiver. He was disappointed: he’d expected a set of servers.

“Shit.” He muttered the word aloud. He’d killed a man for a laptop? There had to be more.

Back in the front room, he found a stack of blank recordable disks, but none that had been used. Where were the used disks? Where? There was a bookcase and he brushed some of the books out, found nothing behind them. Hurried past all the open doors and cupboards, feeling the pressure of time on his shoulders. Where?

He looked, but he found nothing more: only the laptop, winking at him from the doorway.

Had to go, had to go.

He stuffed the paper towels in his pocket, hurried to the door, picked up the laptop, power supply, and recharging deck, pulled the door almost shut with his bare hand, realized what he’d done, took the paper towels out of his pocket, wiped the knob and gripped it with the towel, and pulled the door shut. Hesitated. Pushed the door open again, crossed to the couch, thoroughly wiped the oxygen cylinder.

All right. Outside again, he stuck the electronics under his arm beneath the raincoat, and strolled as calmly as he could to the car. The car, a nondescript Toyota Corolla, had belonged to his mother. It wouldn’t get a second glance anywhere, anytime. Which was lucky, he thought, considering what had happened.

He put the laptop, still running, on the passenger’s seat. The laptop would take very careful investigation. As he drove away, he thought about his exposure in Bobby’s death. Not much, he thought, unless he was brutally unlucky. A neighbor trying a new camera, an idiot savant who remembered his license plate number; one chance in a million.

Less than that, even-he’d been obsessively careful in his approach to the black man; that he’d come on a rainy day was not an accident. Maybe, he thought, he’d known in his heart that Bobby would end this day as a dead man.

Maybe. As he turned the corner and left the neighborhood, a hum of satisfaction began to vibrate through him. He felt the skull crunching again, saw the body fly from the wheelchair, felt the rush…

Felt the skull crunch… and almost drove through a red light.

He pulled himself back: he had to get out of town safely. This was no time for a traffic ticket that would pin him to Jackson, at this moment, at this place.

He was careful the rest of the way out, but still…

He smiled at himself. Felt kinda good, Jimmy James.

HUH! WHACK! Rock ’n’ roll.

Chapter Two

FROM MY KITCHEN WINDOW in St. Paul, over the top of the geranium pot, I can see the Mississippi snaking away to the south past the municipal airport and the barge yards. There’s always a towboat out there, rounding up a string of rust-colored barges, or a guy heading downstream in a houseboat, or a seaplane lining up for takeoff. I never get tired of it. I wish I could pipe in all the sounds and smell of it, leaving out the stink and groan of the trucks and buses that run along the river road.

I was standing there, scratching the iron-sized head of the red cat, when the phone rang.

I thought about not answering it-there was nobody I particularly cared to talk to that day-but the ringing continued. I finally picked it up, annoyed, and found a smoker’s voice like a rusty hinge in a horror movie. An old political client. He asked me to do a job for him. “It’s no big deal,” he rasped.

“You lie like a Yankee carpetbagger,” I said back. I hadn’t talked to him in years, but we were picking up where we left off: friendly, but a little contentious.

“I resemble that remark,” he said. “Besides, it’ll only take you a few days.”

“How much you paying?”

“Wull… nothin’.”

Bob was a Democrat from a conservative Mississippi district. He was worried about a slick, good-looking young Republican woman named Nosere.

“I’ll tell you the truth, Kidd: the bitch is richer than Davy Crockett and can self-finance,” said the congressman. He was getting into his stump rhythms: “When it comes to ambition, she makes Hillary Clinton look like the wallflower at a Saturday-night sock-hop. She makes Huey Long look like a guppy. You gotta get your ass down there, boy. Dig this out for me.”

“You oughta be able to self-finance your own self,” I said. “You’ve been in Washington for twelve years now, for Christ’s sakes.”

Pause, as if thinking, or maybe contemplating the balances in off-shore checking accounts. Then, “Don’t dog me around, Kidd. You gonna do this, or what?”

WHEN all the bullshit is dispensed with, I am an artist-a painter-and for most of my life, in the eyes of the law, a criminal, though I prefer to think of myself as a libertarian who liberates for money.

At the University of Minnesota, where I had gone to school on a wrestling scholarship, I carried a minor in art, with a major in computer science. Computers and mathematics interested me in the same way that art did, and I worked hard at them. Then the Army came along and gave me a few additional skills. When I got out of the service, I went to work as a freelance computer consultant.

Aboveground, I was writing political-polling software that could be run in the new desktop computers, the early IBMs, and even a package that you could run on a Color Computer, if anybody remembers those. I was also debugging commercial computer-control programs, a job that was considered the coal mine of the computer world. I was pretty good at it: Bill Gates had once said to me, “Hey, dude, we’re starting a company.”

Underground, I was doing industrial espionage for a select clientele, entering unfriendly places, either electronically or physically, and copying technical memos, software, drawings, anything that my client could use to keep up with the Gateses. The eighties were good to me, but the nineties had been hot: a dozen technical memos, moved from A to B, could result in a hundred-million-dollar Internet IPO. Or, more likely, could kill one.

All that time, I’d been painting. I can’t tell you about whiskey and drugs and gambling and women, because those things are for amateurs and rock musicians. I worked all the time-maybe dabbled a little in women. Unlike whiskey, drugs, and gambling addictions, I’d found that women tended to go away after a while. On their own.

As did the political-polling business. I sold out to a competitor because I was losing patience with my clients, with my clients’ way of making a living.

Politicians fuck with people. That’s what they do. That’s their job. Every day, they get up and wonder who they’re gonna fuck with that day. Then they go and do it. They’re not of much use-they don’t make anything, create anything, think any great thoughts. They just fuck with the rest of us. I got tired of talking to them.

So the years went by, with painting and computers, and now here I was, talking to Congressman Bob. I wheedled and begged, even pled poverty, but eventually said I’d do it-truth be told, I needed a break from the fever dreams of my latest

paintings, a suite of five commissioned by a rich lumberman from Louisiana.

Then there was my love life, which had taken an ugly turn for the worse.

Getting out of town didn’t look that bad. That’s why, for the past two weeks, I’d been working in the belly of the Wisteria.

THE Wisteria was a casino and hung off a pier on the Gulf Coast of Mississippi, between Biloxi and Gulfport. Designed to look like a riverboat, it was the size of a battleship. Sweeping decks of slot machines, which would take everything down to your last nickel, sucked up most of the space. There were also three restaurants, two bars, and a poop deck for the low-return games.

Muzak, mostly orchestrated versions of old Sinatra sounds, kept you happy while you cranked the slots, and gave the place its class. All of it smelled of tobacco, alcohol, spoiled potato chips, sweat, cleaning fluids, and overstressed deodorant, with just the faintest whiff of vomit.

I was inside for six hours a day, thinking about painting and women, while throwing money down the slot machines. The job was simple enough, but I had to be careful: if I screwed it up, some bent-nosed cracker thug would take me out in the woods and break my arms and legs-if I was lucky.

Or, I should say, our arms and legs.

MY friend LuEllen had come along. She actually liked casinos, and I needed the help. She was also doing therapy on me: she referred to my lost love as Boobs, and had worked out a complete set of verbs and adjectives based on that root word. The day before, in the Wisteria’s fine-dining restaurant (“The best surf-and-turf between New Orleans and Tallahassee ”), she’d held up a glob of deepfried potato and said, “Now there’s one boobilicious Tater Tot.”

“You give me any more shit, I’m gonna stick a Tater Tot in one of your crevices,” I said, with more snarl than I’d intended.

Field of Prey

Field of Prey The Best American Mystery Stories 2017

The Best American Mystery Stories 2017 Mad River

Mad River Storm Front

Storm Front Night Prey

Night Prey Certain Prey

Certain Prey Heat Lightning

Heat Lightning Eyes of Prey

Eyes of Prey Golden Prey

Golden Prey Lucas Davenport Novels 6-10

Lucas Davenport Novels 6-10 The Night Crew

The Night Crew Broken Prey

Broken Prey Mortal Prey

Mortal Prey Dark of the Moon

Dark of the Moon Twisted Prey

Twisted Prey Stolen Prey

Stolen Prey Deadline

Deadline Secret Prey

Secret Prey Rules of Prey

Rules of Prey Extreme Prey

Extreme Prey Bad Blood

Bad Blood Gathering Prey

Gathering Prey Rough Country

Rough Country Sudden Prey

Sudden Prey Silken Prey

Silken Prey Buried Prey

Buried Prey Invisible Prey

Invisible Prey Silent Prey

Silent Prey Deep Freeze

Deep Freeze Bloody Genius

Bloody Genius Naked Prey

Naked Prey Winter Prey

Winter Prey Dead Watch

Dead Watch Escape Clause

Escape Clause Neon Prey

Neon Prey The Fool's Run

The Fool's Run Mind Prey

Mind Prey Easy Prey

Easy Prey The Devil's Code

The Devil's Code Chosen Prey

Chosen Prey The Lucas Davenport Collection, Books 11-15

The Lucas Davenport Collection, Books 11-15 Shock Wave

Shock Wave Shadow Prey

Shadow Prey Naked Prey ld-14

Naked Prey ld-14 Lucas Davenport Novels 16-20

Lucas Davenport Novels 16-20 Invisible prey ld-17

Invisible prey ld-17 Lucas Davenport Collection: Books 11-15

Lucas Davenport Collection: Books 11-15 Masked Prey

Masked Prey![[Prey 11] - Easy Prey Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/22/prey_11_-_easy_prey_preview.jpg) [Prey 11] - Easy Prey

[Prey 11] - Easy Prey Silent Prey ld-4

Silent Prey ld-4 Storm prey ld-20

Storm prey ld-20 Eyes of Prey ld-3

Eyes of Prey ld-3 Certain prey ld-10

Certain prey ld-10 Lucas Davenport Collection

Lucas Davenport Collection Sudden prey ld-8

Sudden prey ld-8 Kidd and LuEllen: Novels 1-4

Kidd and LuEllen: Novels 1-4 Silken Prey ld-23

Silken Prey ld-23 Mad River vf-6

Mad River vf-6 Bad blood vf-4

Bad blood vf-4 Broken Prey ld-16

Broken Prey ld-16 Stolen Prey p-22

Stolen Prey p-22 Night Prey ld-6

Night Prey ld-6 Outrage

Outrage Mind prey ld-7

Mind prey ld-7 Shock Wave vf-5

Shock Wave vf-5 Easy Prey ld-11

Easy Prey ld-11 Prey 7 - Mind Prey

Prey 7 - Mind Prey Winter Prey ld-5

Winter Prey ld-5 Holy Ghost

Holy Ghost Uncaged

Uncaged Rampage

Rampage Hidden Prey ld-15

Hidden Prey ld-15 Buried Prey p-21

Buried Prey p-21 Secret Prey ld-9

Secret Prey ld-9 Chosen Prey ld-12

Chosen Prey ld-12 Phantom prey ld-18

Phantom prey ld-18 Mortal Prey ld-13

Mortal Prey ld-13 Saturn Run

Saturn Run Wicked Prey

Wicked Prey The Hanged Man’s Song

The Hanged Man’s Song Rough country vf-3

Rough country vf-3 Prey 25 - Gathering Prey

Prey 25 - Gathering Prey