- Home

- John Sandford

The Devil's Code

The Devil's Code Read online

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events or locales is entirely coincidental.

The Devil’s Code

A Berkley Book / published by arrangement with the author

All rights reserved.

Copyright © 2000 by John Sandford

This book may not be reproduced in whole or part, by mimeograph or any other means, without permission. Making or distributing electronic copies of this book constitutes copyright infringement and could subject the infringer to criminal and civil liability.

For information address:

The Berkley Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Putnam Inc.,

375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014.

The Penguin Putnam Inc. World Wide Web site address is

http://www.penguinputnam.com

ISBN: 1-101-14663-X

A BERKLEY BOOK®

Berkley Books first published by The Berkley Publishing Group, a member of Penguin Putnam Inc.,

375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014.

BERKLEY and the “B” design are trademarks belonging to Penguin Putnam Inc.

Electronic edition: April, 2004

Titles by John Sandford

RULES OF PREY

SHADOW PREY

EYES OF PREY

SILENT PREY

WINTER PREY

NIGHT PREY

MIND PREY

SUDDEN PREY

SECRET PREY

CERTAIN PREY

EASY PREY

THE NIGHT CREW

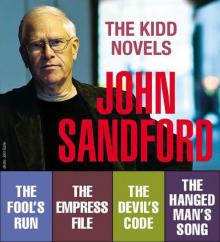

The Kidd Novels

THE EMPRESS FILE

THE FOOL’S RUN

THE DEVIL’S CODE

For Pat and Ray Johns

Contents

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

author’s note

1

ST. JOHN CORBEIL

A beautiful fall night in Glen Burnie, a Thursday, autumn leaves kicking along the streets. A bicycle with a flickering headlamp, a dog running alongside, a sense of quiet. A good night for a cashmere sportcoat or small black pearls at an intimate restaurant down in the District; maybe white Notre Dame–style tapers and a rich controversial senator eating trout with a pretty woman not his wife. Like that.

Terrence Lighter would have none of it.

Not tonight, anyway. Tonight, he was on his own, walking back from a bookstore with a copy of SmartMoney in his hand and a pornographic videotape in his jacket pocket. He whistled as he walked. His wife, April, was back in Michigan visiting her mother, and he had a twelve-pack of beer in the refrigerator and a bag of blue-corn nachos on the kitchen counter. And the tape.

The way he saw it was this: he’d get back to the house, pop a beer, stick the tape in the VCR, spend a little time with himself, and then switch over to Thursday Night Football. At halftime, he’d call April about the garden fertilizer. He could never remember the numbers, 12-6-4 or 6-2-3 or whatever. Then he’d catch the second half of the game, and after the final gun, he’d be ready for the tape again.

An unhappy thought crossed his mind. Dallas: What the hell were they doing out in Dallas, with those recon photos? Where’d they dig those up? How’d that geek get his hands on them? Something to be settled next week. He hadn’t heard back from Dallas, and if he hadn’t heard by Monday afternoon, he’d memo the deputy director just to cover his ass.

That was for next week. Tonight he had the tape, the beer, and the nachos. Not a bad night for a fifty-three-year-old, high-ranking bureaucrat with a sexually distant wife. Not bad at all . . .

Lighter was a block and a half from his home when a man stepped out of a lilac bush beside a darkened house. He was dressed all in black, and Lighter didn’t see him until the last minute. The man said nothing at all, but his arm was swinging up.

Lighter’s last living thought was a question. “Gun?”

A silenced 9mm. The man fired once into Lighter’s head and the impact twisted the bureaucrat to his right. He took one dead step onto the grass swale and was down. The man fired another shot into the back of the dead man’s skull, then felt beneath his coat for a wallet. Found it. Felt the videotape and took that, too.

He left the body where it had fallen and ran, athletically, lightly, across the lawn, past the lilac, to the back lot line, and along the edge of a flower garden to the street. He ran a hundred fifty yards, quiet in his running shoes, invisible in his black jogging suit. He’d worked out the route during the afternoon, spotting fences and dogs and stone walls. A second man was waiting in the car on a quiet corner. The shooter ran up to the corner, slowed, then walked around it. If anyone had been coming up the street, they wouldn’t have seen him running . . .

As they rolled away, the second man asked, “Everything all right?”

“Went perfect.” The shooter dug through the dead man’s wallet. “We even got four hundred bucks and a fuck flick.”

They were out again the next night.

This time, the target was an aging ’70s rambler in the working-class duplex lands southwest of Dallas. A two-year-old Porsche Boxster was parked in the circular driveway in front of the house. Lights shone from a back window, and a lamp with a yellow shade was visible through a crack in the drapes of the big front window. The thin odor of bratwurst was in the air—a backyard barbecue, maybe, at a house farther down the block. Kids were playing in the streets, a block or two over, their screams and shouts small and contained by the distance, like static on an old vinyl disk.

The two men cut across a lawn as dry as shredded wheat and stepped up on the concrete slab that served as a porch. The taller of the two touched the pistol that hung from his shoulder holster. He tried the front door: locked.

He looked at the shorter man, who shrugged, leaned forward, and pushed the doorbell.

John James Morrison was the same age as the men outside his door, but thinner, taller, without the easy coordination; a gawky, bespectacled Ichabod Crane with a fine white smile and a strange ability to draw affection from women. He lived on cinnamon-flavored candies called Hot Tamales and diet Coke, with pepperoni pizza for protein. He sometimes shook with the rush of sugar and caffeine, and he liked it.

The men outside his door stressed exercise and drug therapy, mixed Creatine with androstenedione and Vitamins E, C, B, and A. The closest Morrison got to exercise was a habitual one-footed twirl in his thousand-dollar Herman Miller Aeron office chair, which he took with him on his cross-country consulting trips.

Morrison and the chair rolled through a shambles of perforated wide-carriage printer paper and diet Coke cans in the smaller of the rambler’s two bedrooms. A rancid, three-day-old Domino’s box, stinking of pepperoni and soured cheese, was jammed into an overflowing trash can next to the desk. He’d do something about the trash later. Right now, he didn’t have the time.

Morrison peered into the flat blue-white glow of the computer screen, struggling with the numbers, checking and rechecking code. An Optimus transportable stereo sat on the floor in the corner, with a stack of CDs on top of the right speaker. Morrison pushed himself out of his chair and bent over the CDs, looked for so

mething he wouldn’t have to think about. He came up with a Harry Connick Jr. disk, and dropped it in the changer. Love Is Here to Stay burbled from the speakers and Morrison took a turn around in the chair. Did a little dance step. Maybe another hit of caffeine . . .

The doorbell rang.

Eleven o’clock at night, and Morrison had no good friends in Dallas, nobody to come calling late. He took another two steps, to the office door, and looked sideways across the front room, through a crack in the front drapes. He could see the front porch. One or two men, their bulk visible in the lamplight. He couldn’t see their faces, but he recognized the bulk.

“Oh, shit.” He stepped back into the office, clicked on a computer file, and dragged it to a box labeled Shredder. He clicked Shred, waited until the confirmation box came up, clicked Yes, I’m sure. The shredder was set to the highest level: if the file was completely shredded, it couldn’t be recovered. But that would take time . . .

He had to make some. He killed the monitors, but let the computer run. He picked up his laptop, turned off the lights in the office, and pulled the door most of the way closed, leaving a crack of an inch or two so they could see the room was dark. Maybe they wouldn’t go in right away, and the shredder would have more time to grind. The laptop he carried into the kitchen, turning it on as he walked. He propped it open on the kitchen counter, and pulled a stool in front of it.

The doorbell rang again and he hurried out the door and called, “Just a minute.” He looked back in the computer room, just a glance, and could see the light blinking on the hard drive. He was shredding only one gigabyte of the twenty that he had. Still, it would take time . . .

He was out of it. The man outside was pounding on the door.

He headed back through the house, snapped on the living room overhead lights to let them know he was coming, looked out through the drapes—another ten seconds gone—and unlocked the front door. “Had to get my pants on,” he said to the two men on the stoop. “What’s up?”

They brought Morrison into the building through the back, up a freight elevator, through a heavily alarmed lock-out room at the top, and into the main security area. Corbeil was waiting.

St. John Corbeil was a hard man; in his early forties, his square-cut face seamed with stress and sun and wind. His blue eyes were small, intelligent, and deeply set beneath his brow ridge; his nose and lips narrow, hawklike. He wore a tight, military haircut, with just a hint of a fifties flattop.

“Mr. Morrison,” he said. “I have a tape I want you to listen to.”

Morrison was nervous, but not yet frightened. There’d been a couple of threats back at the house, but not of violence. If he didn’t come with them, they’d said, he would be dismissed on the spot, and AmMath would sue him for violating company security policies, industrial espionage, and theft of trade secrets. He wouldn’t work for a serious company again, they told him.

The threats resonated. If they fired him, and sued him, nobody would hire him again. Trust was all-important, when a company gave a man root in its computer system. When you were that deep in the computers, everything was laid bare. Everything. On the other hand, if he could talk with them, maybe he could deal. He might lose this job, but they wouldn’t be suing him. They wouldn’t go public.

So he went with them. He and the escort drove in his car—“So we don’t have to drag your ass all the way back here,” the security guy said—while the second security agent said he’d be following. He hadn’t yet shown up.

So Morrison stood, nervously, shoulders slumped, like a peasant dragged before the king, as Corbeil pushed an audiotape into a tape recorder. He recognized the voice: Terrence Lighter. “John, what the hell are you guys doing out there? This geek shows up on my doorstep . . .”

Shit: they had him.

He decided to tough it out. “I came across what I thought was anomalous work—nothing to do with Clipper, but it was obviously top secret and the way it was being handled . . . it shouldn’t have been handled that way,” Morrison told Corbeil. He was standing like a petitioner, while Corbeil sat in a terminal chair. “When I was working at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, I was told that if I ever found an anomaly like that, I should report it at least two levels up, so that it couldn’t be hidden and so that security problems could be fixed.”

“So you went to Lighter?”

“I didn’t think I had a choice. And you should remember that I did talk to Lighter,” Morrison said. “Now, I think, we should give the FBI a ring. See what they say.”

“You silly cunt.” Corbeil slipped a cell phone from a suit pocket, punched a button, waited a few seconds, then asked, “Anything?” Apparently not. He said, “Okay. Drop the disks. We’re gonna go ahead on this end.”

Corbeil’s security agent, who’d been waiting patiently near the door, looked at his watch and said, “If we’re gonna do it, we better get it done. Goodie’s gonna be starting up here in the next fifteen minutes and I gotta run around the building and get in place.”

Corbeil gave Morrison a long look, and Morrison said, “What?”

Corbeil shook his head, got up, stepped over to the security agent, and said, “Let me.”

The agent slipped out his .40 Smith and handed it to Corbeil, who turned and pointed it at Morrison.

“You better tell us what you did with the data or you’re gonna get your ass hurt real bad,” he said quietly.

“Don’t point the gun at me; don’t point the gun . . .” Morrison said.

Corbeil could feel the blood surging into his heart. He’d always liked this part. He’d shot the Iraqi colonels and a few other ragheads and deer and antelope and elk and javelina and moose and three kinds of bear and groundhogs and prairie dogs and more birds than he could count; and it all felt pretty good.

He shot Morrison twice in the chest. Morrison didn’t gape in surprise, stagger, slap a hand to his wounds, or open his eyes wide in amazement. He simply fell down.

“Christ, my ears are ringing,” Corbeil said to the security agent. He didn’t mention the sudden erection. “Wasn’t much,” he said. “Nothing like Iraq.”

But his hand was trembling when he passed over the gun. The agent had seen it before, hunting on the ranch.

“Let’s get the other shot done,” the agent said.

“Yes.” They got the .38 from a desk drawer, wrapped Morrison’s dead hand around it, and fired it once into a stack of newspapers.

“So you better get going,” Corbeil said. “I’ll dump the newspapers.”

“I’ll be to Goodie’s right. That’s your left,” the agent said.

“I know that,” Corbeil said impatiently.

“Well, Jesus, don’t forget it,” the agent said.

“I won’t forget it,” Corbeil snapped.

“Sorry. But remember. Remember. I’ll be to your left. And you gotta reload now, and take the used shell with you . . .”

“I’ll remember it all, William. This is my life as much as it is yours.”

“Okay.” The agent’s eyes drifted toward the crumbled form of Morrison. “What a schmuck.”

“We had no choice; it was a million-to-one that he’d find that stuff,” Corbeil said. He glanced at his watch: “You better move.”

Larry Goodie hitched up his gun belt, sighed, and headed for the elevators. As he did, the alarm buzzed on the employees’ door and he turned to see William Hart checking through with his key card.

“Asshole,” Goodie said to himself. He continued toward the elevators, but slower now. Only one elevator ran at night, and Hart would probably want a ride to the top. As Hart came through, Goodie pushed the elevator button and found a smile for the security man.

“How’s it going, Larry?” Hart asked.

“Slow night,” Goodie said.

“That’s how it’s supposed to be, isn’t it?” Hart asked.

“S’pose,” Goodie said.

“When was the last time you had a fast night?”

Goodie knew he wa

s being hazed and he didn’t like it. The guys from TrendDirect were fine. The people with AmMath, the people from “Upstairs,” were assholes. “Most of ’em are a little slow,” he admitted. “Had some trouble with the card reader that one time, everybody coming and going . . .”

The elevator bell dinged at the tenth floor and they both got off. Goodie turned left, and Hart turned right, toward his office. Then Hart touched Goodie’s sleeve and said, “Larry, was that lock like that?”

Goodie followed Hart’s gaze: something wrong with the lock on Gerald R. Kind’s office. He stepped closer, and looked. Somebody had used a pry-bar on the door. “No, I don’t believe it was. I was up here an hour ago,” Goodie said. He turned and looked down the hall. The lights in the security area were out. The security area was normally lit twenty-four hours a day.

“We better check,” Hart said, dropping his voice.

Hart eased open the office door, and Goodie saw that another door, on the other side, stood open. “Quiet,” Hart whispered. He led the way through the door, and out the other side, into a corridor that led to the secure area. The door at the end of the hall was open, and the secure area beyond it was dark.

“Look at that screen,” Hart whispered, as they slipped down the hall. A computer screen had a peculiar glow to it, as if it had just been shut down. “I think there’s somebody in there.”

“I’ll get the lights,” Goodie whispered back. His heart was thumping; nothing like this had ever happened.

“Better arm yourself,” Hart said. Hart slipped an automatic pistol out of a belt holster, and Goodie gulped and fumbled out his own revolver. He’d never actually drawn it before.

“Ready?” Hart asked.

“Maybe we ought to call the cops,” Goodie whispered.

“Just get the lights,” Hart whispered. He barely breathed the words at the other man. “Just reach through, the switch is right inside.”

Goodie got to the door frame, reached inside with one hand, and somebody screamed at him: “NO!”

Goodie jerked around and saw a ghostly oval, a face, and then WHAM! The flash blinded him and he felt as though he’d been hit in the ribs with a ball bat. He went down backwards, and saw the flashes from Hart’s weapon straight over his head, WHAM WHAM WHAM WHAM . . .

Field of Prey

Field of Prey The Best American Mystery Stories 2017

The Best American Mystery Stories 2017 Mad River

Mad River Storm Front

Storm Front Night Prey

Night Prey Certain Prey

Certain Prey Heat Lightning

Heat Lightning Eyes of Prey

Eyes of Prey Golden Prey

Golden Prey Lucas Davenport Novels 6-10

Lucas Davenport Novels 6-10 The Night Crew

The Night Crew Broken Prey

Broken Prey Mortal Prey

Mortal Prey Dark of the Moon

Dark of the Moon Twisted Prey

Twisted Prey Stolen Prey

Stolen Prey Deadline

Deadline Secret Prey

Secret Prey Rules of Prey

Rules of Prey Extreme Prey

Extreme Prey Bad Blood

Bad Blood Gathering Prey

Gathering Prey Rough Country

Rough Country Sudden Prey

Sudden Prey Silken Prey

Silken Prey Buried Prey

Buried Prey Invisible Prey

Invisible Prey Silent Prey

Silent Prey Deep Freeze

Deep Freeze Bloody Genius

Bloody Genius Naked Prey

Naked Prey Winter Prey

Winter Prey Dead Watch

Dead Watch Escape Clause

Escape Clause Neon Prey

Neon Prey The Fool's Run

The Fool's Run Mind Prey

Mind Prey Easy Prey

Easy Prey The Devil's Code

The Devil's Code Chosen Prey

Chosen Prey The Lucas Davenport Collection, Books 11-15

The Lucas Davenport Collection, Books 11-15 Shock Wave

Shock Wave Shadow Prey

Shadow Prey Naked Prey ld-14

Naked Prey ld-14 Lucas Davenport Novels 16-20

Lucas Davenport Novels 16-20 Invisible prey ld-17

Invisible prey ld-17 Lucas Davenport Collection: Books 11-15

Lucas Davenport Collection: Books 11-15 Masked Prey

Masked Prey![[Prey 11] - Easy Prey Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/22/prey_11_-_easy_prey_preview.jpg) [Prey 11] - Easy Prey

[Prey 11] - Easy Prey Silent Prey ld-4

Silent Prey ld-4 Storm prey ld-20

Storm prey ld-20 Eyes of Prey ld-3

Eyes of Prey ld-3 Certain prey ld-10

Certain prey ld-10 Lucas Davenport Collection

Lucas Davenport Collection Sudden prey ld-8

Sudden prey ld-8 Kidd and LuEllen: Novels 1-4

Kidd and LuEllen: Novels 1-4 Silken Prey ld-23

Silken Prey ld-23 Mad River vf-6

Mad River vf-6 Bad blood vf-4

Bad blood vf-4 Broken Prey ld-16

Broken Prey ld-16 Stolen Prey p-22

Stolen Prey p-22 Night Prey ld-6

Night Prey ld-6 Outrage

Outrage Mind prey ld-7

Mind prey ld-7 Shock Wave vf-5

Shock Wave vf-5 Easy Prey ld-11

Easy Prey ld-11 Prey 7 - Mind Prey

Prey 7 - Mind Prey Winter Prey ld-5

Winter Prey ld-5 Holy Ghost

Holy Ghost Uncaged

Uncaged Rampage

Rampage Hidden Prey ld-15

Hidden Prey ld-15 Buried Prey p-21

Buried Prey p-21 Secret Prey ld-9

Secret Prey ld-9 Chosen Prey ld-12

Chosen Prey ld-12 Phantom prey ld-18

Phantom prey ld-18 Mortal Prey ld-13

Mortal Prey ld-13 Saturn Run

Saturn Run Wicked Prey

Wicked Prey The Hanged Man’s Song

The Hanged Man’s Song Rough country vf-3

Rough country vf-3 Prey 25 - Gathering Prey

Prey 25 - Gathering Prey